Perceptions and Practices on Postharvest Management Investment for Resilient Livelihoods in Uporoto Highlands of Tanzania

Brown Gwambene*

University of Iringa, Tanzania

| ARTICLE INFORMATION | ABSTRACT |

| Corresponding author: Brown Gwambene E-mail: gwambene@gmail.com Keywords: Postharvest loss Food security Smallholder farmer’s Production process Resilient livelihoods Received: 17.05,2923 Received in revised form: 22.05.2023 Accepted:25.05.2023 | Sub-Saharan Africa experiences seasonal loss of millions of tons of food and produces due to low postharvest infrastructure investment. Postharvest loss impedes the achievement of SDG 2 of Zero Hunger, which aims to end hunger, achieve food security and nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture by 2030. This study employed a survey method to assess postharvest management for reducing food loss and waste among smallholder farmers, using questionnaire surveys, key informant interviews, and field observations. The data collected were analyzed thematically, and trend analysis for qualitative data and SPSS and Microsoft Excel for quantitative data. Results revealed that a lack of investment in postharvest management is responsible for about 90% of crop loss, food shortage, and loss of income. Challenges highlighted during the study included poor storage, production systems, processing knowledge, cultural aspects, storage infrastructure, seasonal markets, and a need for more supportive environments. Packing in bags (71%) and the roof of the house (ceiling board) 97% were common postharvest preservation and storage methods, with negative repercussions on postharvest management. The study recommends promoting investment in postharvest management, improving knowledge, infrastructure, production, processing, storage, and distribution systems to reduce food loss and waste. |

INTRODUCTION

Strengthening postharvest management is crucial to address smallholder farmers’ challenges and modernize agricultural production. Postharvest losses in developing countries exacerbate food insecurity and result in significant welfare loss for farming households (Tesfaye and Tirivayi, 2018). Cereal grains are particularly vulnerable to postharvest losses, with losses as high as 30 to 50 percent reported in the literature (Befikadu, 2018).

These losses can affect the quality and quantity of the produced crops, leading to lost income and value. Therefore, reducing postharvest losses has become a primary concern for achieving food security and increasing productivity through modern agricultural production (Ridolfi et al.2018).

Postharvest losses include food losses along the supply chain and food wastage at the consumer level (Parmar et al. 2018; Braun et al., 2019). Several factors responsible for postharvest losses include climate change and variability, incidents of insect, pest, and fungal infestation, inadequate storage strategies and poor infrastructures. Santeramo (2021) and Yimer (2022) indicated that cereal crops are more affected by postharvest loss from insect, pest, and fungal infestation and inadequate storage and crop management systems. Braun et al. (2019) identified

the underlying factors and consumers’ food waste behavior resulting from conflicting goals, such as convenience, taste, and saving. It was noted that food waste highlights the inequity of the food system at the household level.

While postharvest losses are primarily initiated at the farm level in developing countries, the problem can persist across the value chain (Ridolfi et al. 2018; Befikadu, 2018). Contributing factors to postharvest losses include outdated harvest techniques, limited postharvest handling and infrastructure, and a lack of suitable agro-climates for generating technology that minimizes losses (Befikadu, 2018).

In addition, postharvest infrastructure, particularly food storage and marketing, contributes to crop production challenges (Bendinelli et al. 2020). The challenges were increased by outdated harvest techniques, limited postharvest handling and storage, and marketing infrastructure. To address these issues, multiple suitable agro-climates with a great effort on generating technology that minimizes loss need to focus on cost-effective options and increase investment in storage technologies.

Reducing postharvest losses is critical for improving food security and safety, reducing unnecessary resource use, and increasing food supply chain actors’ profits (Bendinelli et al. 2020). It is especially crucial in sub-Saharan Africa, where low investment in postharvest infrastructure has resulted in a seasonal loss of millions of tons of food and produce.

Moreover, postharvest loss reduction is essential to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 of Zero Hunger, which targets ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture by 2030. In addition, the availability of cost-effective storage options has increased farmers’ willingness to invest in safe storage technologies, such as various hermetic technologies (Njoroge et al. 2019).

Building awareness of improved storage technologies, finding solutions for pest infestations in the field and after harvest, and investing in postharvest infrastructure is vital for reducing postharvest losses. Postharvest losses do not include food waste in retail markets or after reaching consumers, which is generally related to retailers’ and consumers’ behaviour (Bendinelli et al. 2020).

Despite the importance of postharvest management investment, perceptions, practices, and knowledge, less investment is animated, especially in low-income countries. Therefore, this work aims to study postharvest management practices to identify practical measures to address the challenges and increase resilience among smallholder farmers.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study area

The study was conducted in the Isongole ward in Uporoto Highlands, Southern Highland of Tanzania. The Highlands extend into three districts Mbeya Rural and Rungwe (Mbeya Region), and Makete (Njombe Region). The area is characterized by high volcanic mountains (Sokoni and Tilumanywa, 2021) with steeply dissected escarpments ranging from Tembela ward in the Mbeya rural district and covering about 10% of the total area of the Rungwe district with an altitude ranging between 2000 – 2865 masl meters above the sea level. The climate is usually relatively cool (50c – 180c), with reliable rainfall ranging from 1500 mm to 2700 mm (Gwambene, 2020) that favour the production of maize, round potatoes, cabbages, peas, fruits pyrethrum, and wheat in the northern part. Farmers in the area primarily produce to meet their basic food requirements, with the booming round potato production as a cash crop. The area was selected due to its economic importance. It is strategically located in the highland region and interconnected with a good tarmac road network from Mbeya City to Rungwe, Kyela, and Malawi (Gwambene, 2022). It has many natural resources, including natural forests and fertile volcanic soils with a booming round potato production (Sokoni and Tilumanywa, 2021). However, the area is also constrained by heavy rainfall, fog, frost, crop pests, and diseases, essential in the postharvest loss.

2.2 Data Source and Methods

The study employed desk review and a survey method to investigate postharvest losses among smallholder farmers. It assesses postharvest management for reducing food loss and waste among smallholder farmers. The techniques used included a questionnaire survey (QS), Key informant interview (KII), and Field Observation (FO) data collection techniques.

Household questionnaire

Data were collected from randomly selected households using a structured questionnaire. The information was gathered through interviews with the head of households. Where the head of the household was unavailable for any reason, a close relative familiar with household activities, income, and expenditure was interviewed instead. The questionnaire gathered information on socio economic, general household characteristics, post harvesting management practices, challenges faced, and opine on sustainability and improving food security.

Focus group discussions: Focus group discussions comprise village Government, men and women: youth, elderly, preeminent farmers, and participants with different social and economic characteristics. The FGD was arranged to involve all other groups based on socio-economic factors (age, gender, education, socio-economic status, and spatial representation) in the selected area. The objective was to have their expressed needs and the constraints they face and gather their perception on postharvest management, challenges, and options for sustainability.

Key informant interviews

The guiding checklist was prepared for gathering information on postharvest management and coordination issues. The targeted respondent groups included expertise from the agricultural sector, Natural resources, land, environment sectors, local government at districts, wards, and village levels, and knowledgeable elders in the community. The interviews were conducted with key respondents guided by a checklist administered to target groups at their places or area of convenience.

Field observations: the technique includes visiting the different locations and households in the study to verify some of the infrastructure and methods used. It involved taking photos and jotting notes and other information in the study area. The technique used to validate and complement the information gathered through other methods.

2.3 Data Organisation and Analysis

Thematic and trend analysis was used for the qualitative data analysis, and SPSS Version 20 and Microsoft Excel software was used for the quantitative data. The analyzed data through SPSS and Microsoft Excel soft wares were presented in percentages,

Tables, Figures, and inferential forms. Besides, the qualitative data were presented in narrative text, tables, and conceptual statements. The study assessed the postharvest management challenges ranging from pre and post-harvesting activities, management practices, and coordination to sustain and improve food security and income of farming households.

3.0 Results

3.1 The production system and postharvest practices

The production system differs among the farms depending on the available resources and constraints, geographical location and climatic conditions, government policy, socio-economic and political pressures, and the farmer’s philosophy. The socio economic factors are affected by household priorities and resource endowments. The study indicates that most crops are affected by harvesting operations, on

farm storage, transport operation, preliminary processing, packaging, sorting, and bagging. Such factors pose tremendous losses on adversity and reduce crop production profitability. Smallholder farmers, over time, develop methods to reduce pre and postharvest loss. Figure 1 indicates the past used postharvest methods; some are still in use.

The past postharvest preservation methods include the roof of the house (ceiling), warehouse, pesticides, use of herbs and spices, and smoking. The cause of postharvest loss is poor production, poor harvesting techniques, limited access to inputs, poor linkage to traders and brokers, and incorrect harvesting. In addition, low-cost and cost-effective postharvest technology adoption is affected by a lack of knowledge and information about such technologies, financial constraints, and farmers’ prioritization of consumption over future income.

3.2 Food storage and storage facilities

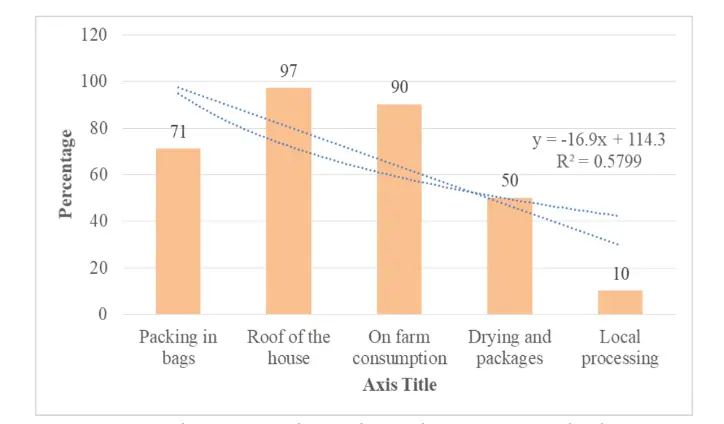

The results indicate poor food storage and storage facility in the area. The situation resulted from the inferior technology and management strategies of the producers. Postharvest preservation methods include packing in bags 71% and storing on the house roofs (Ceiling) 97% (especially for maize). Figure 2 indicates the postharvest methods used for main food crops.

Figure 2 indicates the most used post-harvesting method among smallholder farmers in the southern highlands. Depending on the nature of the crops produced, smallholder farmers apply methods that include storing on the roof of the house (especially for maize and regimes), on-farm consumption (some crops utilized directly from the farm), packing in bags, drying and packaging, and local processing.

The most used post-harvesting preservation and storage methods for maize are packing in bags and roof of the house. Round potatoes are primarily packed in bags for business purposes. The preservation and storage methods used have repercussions on postharvest management.

Among the challenges of postharvest management are the seasonal market and the need for access to appropriate processing equipment. The seasonal market depends on the harvesting season, which usually has its peak. Changes in timing, weather, and sociocultural and political situation can increase seasonal demands, processing, and storage challenges.

Figure 1 Past used postharvest preservation methods

Figure 2 The commonly used post-harvesting method

3.3 Postharvest handling practices and management challenges

The practices of handling harvest from farms and commodities from the purchasing point up to their marketplace increased challenges in postharvest management. The study noted the practices which promote and that reduce postharvest losses.

The results indicate that a lack of investment in postharvest management causes about 90% of crop loss, food shortage, and loss of income among smallholder farmers. The situation is augmented by poor handling practices, limited access to on-farm storage, and inadequate transportation.

The persisting and pressing postharvest management challenges highlighted during the study included poor storage, production system, lack of processing knowledge and packaging facilities, cultural aspects, poor storage infrastructure, seasonal market, supportive environment, and institutional support (Figure 3).

The seasonal market is conducted during harvesting, and the cultural aspects involve community consumption and preferences. The study by Chebanga et al. (2018) noted changes in food consumption habits that affect the postharvest chain.

Thus, promoting postharvest management investment is needed by improving knowledge, infrastructure, production process, processing, and storage facilities lead to higher postharvest harvest losses. Therefore, farmers are encouraged to improve their production by improving product quality and reducing harvesting, processing, packaging, transportation, marketing, and storage challenges.

Figure 3. The postharvest management challenges among smallholders farmers

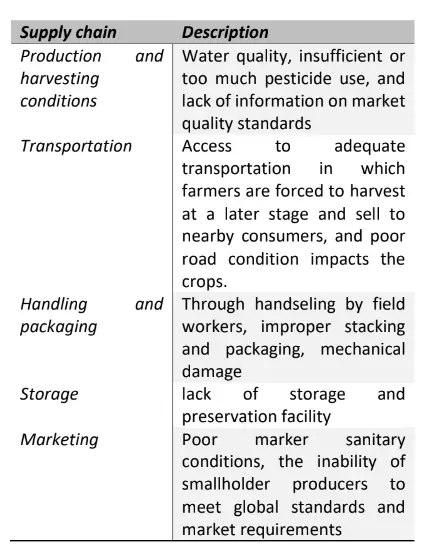

Table 1. The description of challenges across the supply chains

The revealed challenges in postharvest management are instigated by harvesting operations, on-farm In addition, poor handling practice, weather condition, inadequate transportation, and lack of access to appropriate processing equipment affects the pre and post harvesting processes (Table 1). Ridolfi et al. (2018) noted similar results indicating challenges in adopting low-cost and cost-effective postharvest technology.

The adoption is affected by a need for knowledge and information about such technologies, financial constraints, and farmers’ prioritization of consumption over future income.

The postharvest losses in poor storage, transportation, and poor packaging significantly affect farmers’ production benefits. For example, Chebanga et al. (2018) indicated poor transportation methods, a considerable distance from the market, and outdated storage, transport operation, preliminary processing, packaging, sorting, and bagging. Poor production, harvesting techniques, linkage to traders and brokers, limited access to inputs, and incorrect harvesting increased management challenges.

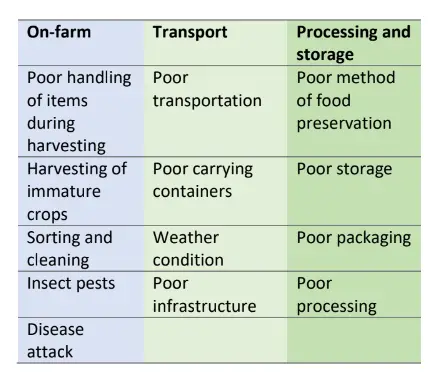

3.4 Cause of postharvest losses

The causes of the postharvest losses experienced across the value chain have multiple and complex forms. Some of the reasons that have resulted in postharvest losses include poor storage, transportation, processing and packaging, and insect pests’ damages (Table 2).

The loss experienced at the farm level to the traders at the marketplace. Losses were also experienced during handling harvests, poor packaging, and transportation, including harvesting immature crops and inadequate carriage facilities. Chebanga et al. (2018) noted similar results from the experience of informal and formal traders. The climatic condition also contributed to the pre, during, and postharvest.

Table 2 Cause of postharvest loss across the process

In the postharvest value chain, loss occurs from production to consumption, whereby, at the production point, part of the crop is lost due to rodents, pests, and diseases. Similarly, a lack of effective harvesting, transport, and storage facilities leads to losses at the farm level. Mndeme (2016) noted that food losses result in lost income for smallholder farmers and higher prices for poor consumers during harvest and storage. Thus, it recommended undertaking a research programme on building resilience through postharvest processing and value addition (FANRPAN, 2016).

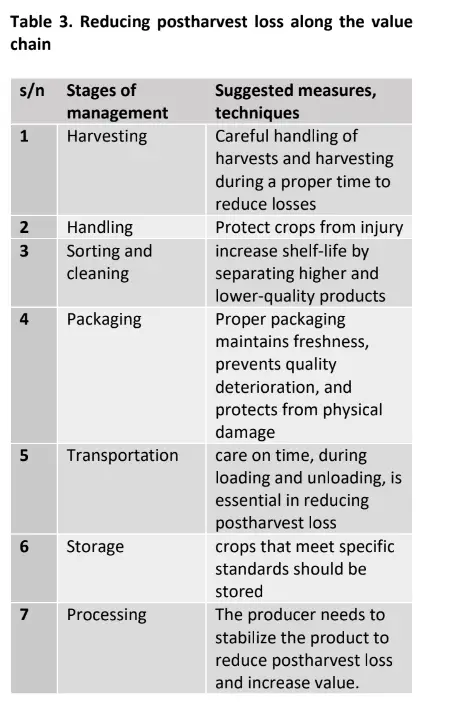

3.5 Measures to minimize postharvest loss

Postharvest loss challenges are observed through the value chain at different stages; thus, such challenges are better addressed along the value chain (Table 3). The technique, innovations, and technologies to reduce postharvest losses include developing varieties with longer shelf-lives while maintaining nutritional properties, taste, and texture, capacity development, and training on specific value chains among farmers and key actors in the value chain. During harvesting, carefully handling harvests and harvesting during a proper time to reduce losses. Crop losses occur before, during, and after harvesting due to inadequate drying, inefficient storage facilities, and lack of appropriate technologies. First, drying in the field and at home, then stored near the house using different containers and technologies.

The smallness of the operational activities and harvests among smallholder farmers affects the postharvest chain and its management. The study noted that aggregating produce from smallholder farmers is critical in improving postharvest management by allowing farmers to access technologies (storage, packaging) and transportation facilities. In addition, smallholders need to have the ability to meet specific quantity, quality, and safety standards to access high market value and preserve of quality of produce (Omotilewa, 2018; Sibanda and Workneh, 2020). Meeting quantity, quality, and product safety standards are critical in accessing high value markets for smallholder farmers.

Thus, linking smallholder producers in the value chain through increasing awareness, access to technology, and coordination is crucial for improving postharvest management, food security, and household income. In addition, capacity building, learning, and applying practical methods to reduce losses across the postharvest value chain are equally important in improving food security and livelihood income.

4.0 Discussions

The study indicates that most crops are affected by postharvest practices such as harvesting operations, on-farm storage, transport operation, preliminary processing, packaging, sorting, and bagging. Such factors pose tremendous losses on adversity and reduce crop production profitability. Storage facilities in the study area could be better, primarily resulting from the producers’ inferior technology and management strategies.

Postharvest preservation methods commonly used among smallholder farmers include packing in bags and storing on the house’s roof (Ceiling) for maize. Round potatoes are primarily packed in bags for business purposes. Outdated harvesting techniques, limited postharvest handling and storage, and marketing infrastructure have contributed to the problem (Bendinelli et al., 2020). The lack of suitable agro-climates for generating technology that minimizes losses also exacerbates the situation (Befikadu, 2018).

The highlighted significant impact of postharvest practices affects crop production and profitability. Various stages of the postharvest process, including harvesting operations, on-farm storage, transport, preliminary processing, packaging, sorting, and bagging, contribute to substantial losses and reduced crop production profitability. The results align with Santeramo (2021), who noted that inappropriate collection, transport, storage, and pest control systems account for approximately 30 to 50 percent of postharvest losses. In addition, postharvest losses encompass food losses along the supply chain, including food wastage at the consumer level (Braun

et al. 2019). Several factors contribute to postharvest losses, including climate change and variability, insect, pest, and fungal infestation incidents, inadequate storage strategies, and poor infrastructure. Cereal crops, in particular, are more susceptible to postharvest losses due to insect, pest, and fungal infestation and inadequate storage and crop management systems (Santeramo, 2021; Yimer, 2022).

Reducing postharvest losses is crucial for achieving food security, ensuring food safety, optimizing resource utilization, and increasing profitability within the food supply chain (Bendinelli et al. 2020). Smallholder farmers have developed methods to mitigate pre and postharvest losses, such as utilizing the roof of their houses, warehouses, pesticides, herbs, and spices, and smoking for preservation.

These findings are consistent with previous studies emphasizing critical technologies and services for reducing food loss (Díaz-Valderrama et al. 2020; Balana et al. 2021). However, adopting low-cost and cost-effective postharvest technologies faces challenges due to limited knowledge and information, financial constraints, and farmers prioritizing immediate consumption over future income.

These findings align with a study by Parmar et al. (2018) and Braun et al. (2019) that identified factors influencing the adoption of postharvest technologies and consumers’ food waste behavior resulting from conflicting goals, convenience, taste, and saving. The issue of food waste further highlights the inequity in the food system at the household level.

According to the literature, a sustainable food system improves food availability and income within the supply chain and reduces food waste (Braun et al. 2019; Balana et al. 2021; Afzal et al. 2019). Enhancing the value chain improves the storability and transportability of produce, ensures product quality, reduces postharvest losses, and enhances food access and price stabilization. Additionally, it improves food utilization by promoting diversification, reducing environmental impact, and implementing postharvest innovations. Reducing postharvest losses also minimizes food contamination and spoilage, significantly contributing to high postharvest losses.

Applying appropriate techniques, utilizing improved inputs such as high-quality seeds or planting materials, and ensuring efficient logistics and marketing improved agricultural production (Yimer, 2022; Balana et al. 2021; Abdullahi and Dandago,2021).

Investing in improved technology leads to increased production yield in smallholder farms and contributes to the overall food supply, job creation, and enhanced livelihoods. However, for an adequate food supply system, equal attention should be given to production and the postharvest supply chain, as they are interconnected elements (Yimer, 2022; Balana et al. 2021; Abdullahi and Dandago, 2021).

It noted the increased application of the proper techniques, improved inputs (like seeds), and appropriate logistics levels and marketing. Investing in improved technology leads to higher production yields in smallholder farms (Yimer, 2022; Balana et al. 2021; Abdullahi and Dandago, 2021).

A higher food supply system improves the total available food volume, creates jobs, and improves livelihoods. Nevertheless, to realize an adequate food supply system, the focus should be on production and the postharvest supply chain as an indissoluble link that creates effective food supply systems (Yimer, 2022; Balana et al. 2021; Abdullahi and Dandago, 2021).

Reducing postharvest losses is vital to achieving food security, safety, and sustainable agriculture. Therefore, investment in storage technologies, building awareness of improved storage technologies, finding solutions for pest infestations in the field and after harvest, and investing in postharvest infrastructure are essential. Braun et al. (2019) discussed the interventions to reduce food waste across supply chains and households.

Postharvest management is vital to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 of Zero Hunger, which targets ending hunger, achieving food security, and promoting sustainable agriculture by 2030. Thus, interventions that focus on generating technology that minimizes losses and increases investment in storage technologies are needed. Besides, smallholder farmers should adopt low-cost and cost effective postharvest technologies, access knowledge and information on technologies, and address production challenges.

5.0 Conclusion and Recommendation

Understanding and improving farmers’ pre and postharvest management practices are crucial for enhancing farming households’ food security and income. Adequate measures must be implemented to identify the most cost-effective and efficient ways to address postharvest loss among smallholder farmers. Aggregating produce from smallholder farmers can

allow farmers to access technologies for processing, packaging, preserving, and storing their products, as well as transportation facilities and reliable markets.

Postharvest losses occur mainly during harvesting, transportation, storage, and marketing, and the mode of transport and transport distance can significantly influence the magnitude of these losses. Therefore, it is essential to create an enabling environment for all key stakeholders, including the private sector, non profit organizations, and the public sector, to invest in postharvest management to address postharvest loss. Public and non-profit actors should coordinate across value chains where the private sector needs more capacity or incentives for investment in postharvest loss reduction. The activities may involve training and capacity building for smallholder farmers and linking them in the value chain through increased awareness and access to grading, sorting, storage, proper packing, and coordination technology. By implementing these measures, we can reduce postharvest losses and improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers.

Declaration of competing interest

The Author declares that the manuscript adheres to the competing interest policy and discloses that all relevant sources, including financial and non-financial interests and relationships, have been acknowledged.

References

Abdullahi, N.; Dandago, M.A. Postharvest losses in food grains – A Review. Turkish Journal of Food and Agriculture Sciences, 2021, 3 (2), 25-36. DOI: 10.53663/turjfas.958473

Afzal, I.; Zahid, S.; Mubeen, S. Tools and Techniques of Postharvest Processing of Food Grains and Seeds. In: Hasanuzzaman, M. (eds) Agronomic Crops. Springer, Singapore, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9783-8_26

Balana, B.B.; Aghadi, C.N.; Ogunniyi, A.I. Improving livelihoods through postharvest loss management: evidence from Nigeria. Food Security, 2021, 14: 249-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01196-2

Befikadu, D. Postharvest Losses in Ethiopia and Opportunities for Reduction: A Review. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 2018, 38 (1): 249–62

Bendinelli, W.E; Su, C.T.; Péra, T.G.; Filho, J.V.C. What are the main factors that determine postharvest losses of grains?. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 2020, 21: 228- 238.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2019.09.002. Braun, J.V.; Sorondo, M.S.; Steiner, R. Reduction of Food Loss and Waste. Conference Proceedings, held at Casina Pio IV, Vatican City: Scripta Varia, 2019, 147.

Chebanga, F.; Mukumbi, K.; Moses, M.; Mtaita, T. Postharvest losses to agricultural product traders in Mutare, Zimbabwe. Journal of Scientific Agriculture, 2018, 2, 26-38. doi: 10.25081/jsa.2018.v2.892 http://updatepublishing.com/journals/index.p hp/jsa

Díaz-Valderrama, J.R.; Njoroge, A.W.; Macedo Valdivia, D.; Orihuela-Ordóñez, N.; Smith, B.W.; Casa-Coila, V.; Ramırez-Calderon, N.; Zanabria Galvez, J.; Woloshuk, C.; Baributsa, D. Postharvest practices, challenges and opportunities for grain producers in Arequipa, Peru. PLoS ONE, 2020, 15(11), e0240857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.024085 7

Gwambene, B. Challenges and opportunities for extenuating and altering the farming production across the gradient of Rungwe District, Tanzania. Discovery Journals, 2020, 56 (291), 150–161. https://tinyurl.com/ybvpvmj5

Gwambene, B. Agricultural Production Dynamics under the Changing Climate in Rungwe District, Tanzania. Eliva Press Global Ltd., part of Eliva Press SRL, 2022. ISBN: 978-99949-8-068-0

Kerra, R.B.; Kangmennaang, J.; Dakishoni, L.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Lupafya, E.; Shumba, L; Msachi, R.; Boatenge, G.O,; Snapp, S.S.; Chitaya, A.; Maona, E.; Gondwe, T.; Nkhonjera, P,; Luginaah, I. Participatory agroecological research on climate change adaptation improves smallholder farmers’ households’ food security and dietary diversity in Malawi. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 2019, 279, 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.04.004

Kuyu, C.G.; Bereka, T.Y. Review the contribution of indigenous food preparation and preservation techniques to attaining food security in Ethiopia. Food Science Nutrition, 2020, 8, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1274

Njoroge, A.W.; Baoua, I.; Baributsa, D. Postharvest Management Practices of Grains in the Eastern Region of Kenya. Journal of Agricultural Science, 2019, 11 (3), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v11n3p33.

Omotilewa, O.J.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Ainembabazi, J.H.; Shively, G.E. Does improved storage technology promote modern input use and food security? Evidence from a randomized trial in Uganda. Journal of Development Economics, 2018, 135, 176–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.07.006

Parmar, A.; Fikre, A.; Sturm, B.; Hensel O. Postharvest management and associated food losses and by-products of cassava in southern Ethiopia. Food Security, 2018, 10 (2): 419-435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0774-7

Pastori, M.; Dondeynaz, C.; Minoungou, B.; Udias, A.; Ameztoy, I.; Hamatan, M.; Cattaneo, L.; Ali, A.; Moreno, C.C.; Ronco, P. Identifying Optimal Agricultural Development Strategies in the West African Sahel Mékrou Transboundary River Basin.Y. Bamutaze et al. (eds.) 2019, Agriculture and Ecosystem Resilience in Sub Saharan Africa, Climate Change Management. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12974-3_33

Ridolfi, C.; Hoffman, V.; Baral, S. Postharvest losses: Global scale, solutions, and relevance to Ghana. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), 2018. http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/132322

Shee, A.; Manyanja, S.; Simba, E.; Stathers, T.; Bechoff, A.; Bennett, B. Determinant of postharvest losses along smallholder producers maize and sweet potato value chains: an ordered Probit analysis. Food Security, 2019, 11, 1101-1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00949-4

Sibanda, S.; Workneh, T.S. Potential causes of postharvest losses, low-cost cooling technology for fresh produce farmers in Sub Sahara Africa. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2020, 16(5), 553-566. DOI: 10.5897/AJAR2020.14714

Sokoni. C.; Tilumanywa, V. ‘Exploring Long-Term Changes in People’s Welfare on the Uporoto Highlands, Mbeya District, Tanzania’, in Brockington, D., and Noe, C. (eds), Prosperity in Rural Africa? Insights into Wealth, Assets, and Poverty from Longitudinal Studies in Tanzania. Oxford, 2021; online edn, Oxford Academic, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198865872. 003.0014, accessed 3 Dec. 2022.

Stathers, T.; Holcroft, D.; Kitinoja, L.; Mvumi, B.M.; English, A.; Omotilewa, O.; Kocher, M.; Ault, J.; Torero, M. A scoping review of crop postharvest loss reduction interventions in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Nature Sustainability, 2020, 3, 821–835.

Tadesse, B.; Bakala, F.; Mariam, L.W. Assessment of postharvest loss along the potato value chain: the case of Sheka Zone, southwest Ethiopia.Agriculture & Food Security. 2018, 7:18

Tesfaye, W.; Tirivayi, N. The Impacts of Postharvest Storage Innovations on Food Security and Welfare in Ethiopia. Food Policy, 2018, 75: 52– 67. 4.

Yimer, H.A. Postharvest Management Practices of Maize in Ethiopia: A Review. Agricultural Science Digest, 2022, 42(5): 521-527. doi: 10.18805/ag.DF-414.

Santeramo, F.B. Exploring the link among food loss, waste and food security: what the research should focus on? Agriculture and Food Security, 2021, 10(26): 1-3.